If you ever find yourself working in an infectious disease laboratory, whether it’s of the diagnostic or research variety, the overarching goal is not to put any microbes in your eye, an open wound or your mouth. Easy enough, right? Wear gloves, maybe goggles, work in fume hoods and don’t mouth pipette. When working with pathogenic bacteria and viruses, priority number one is Do Not Self-Inoculate.

This is obvious for anyone who has worked in a shiny biology or chemistry lab or seen an episode of CSI: Crime Scene Investigation (we’re all friends here, just admit it), but one of the most commonly used pieces of equipment in labs prior to the 1970s was the leading cause of laboratory-derived infections: the honorable pipette. How could that be possible, you ask? By using one’s oral cavity with the pipette to measure and transfer liquids.

Today our manual pipettes are rather sophisticated, plastic-y devices perfectly calibrated for moving precisely exact milliliters, microliters and picoliters of valuable solution from one vessel to another, whether it’s of a urine sample, some spare radioactive material you have lying about or toxic solvents. But before the development of cheap mechanical pipettes in the ’70s, using your mouth to pipette solutions was more than a common sight, it was a way of the lab.

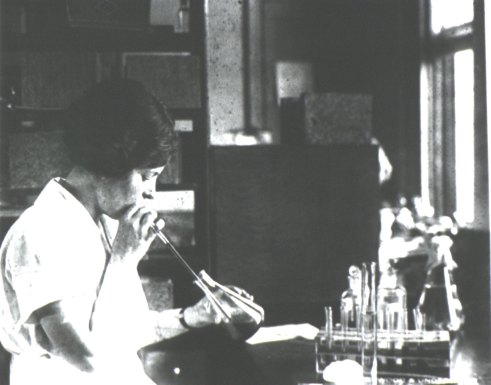

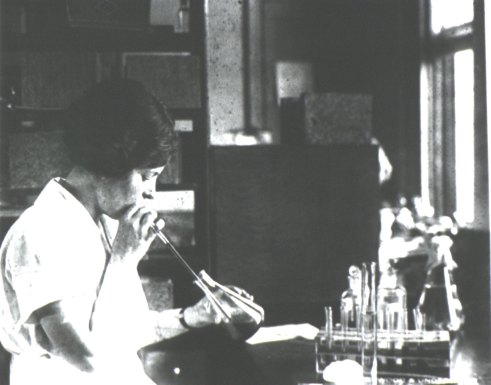

Former Centers for Disease Control (CDC) parasitologist, Dr. Mae Melvin (Lt), examines a collection of test tubes while her laboratory assistant mouth pipettes a culture to be added to these test tubes. Source: David Senser/CDC.

Don’t worry, reader, I heard you tentatively whisper, “just what exactly is mouth pipetting, dare I ask?”

Like so: insert an open-ended glass capillary tube into your mouth. Place the opposite, tapered end of the tube into a solution of your choice. Microbial stews, blood, cell culture, it is totally your call. With a method that carefully mimics the sucking of a straw, draw a solution upwards through your man-made pipette to your desired volume using the tension created by the reduced air pressure – yes, suction! Maintain the tension with your mouth. Do not suck too hard and inadvertently slurp the solution into your mouth. Careful now. Gently move the pipette end from one vessel and release your precious cargo into yet another vessel.

That is mouth pipetting.

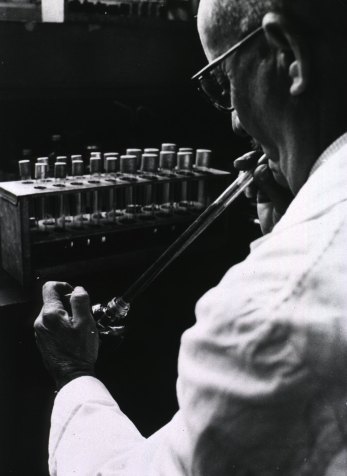

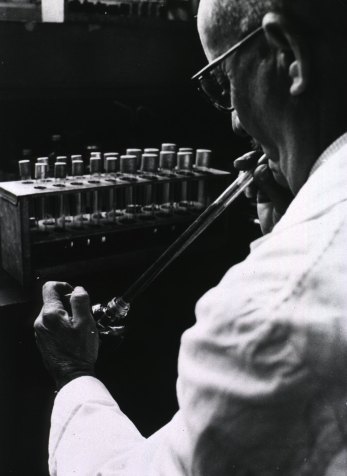

A wonderful demonstration of mouth pipetting by Dr. Armand Frappier, a microbiologist and expert on tuberculosis. Look closely: you can see him draw a dark liquid slowly towards his mouth. What could it be? Soda, a culture of TB, serum for cell cultures? You can watch the entire video clip that this GIF is based upon here. Source: Musée Armand Frapper.

The sparsity of history on pipetting techniques (itself a shocking shortcoming, I’m sure you’ll agree), forbids us from generalizing the prevalence of this phenomena. But we do know that it was the source of a ridiculous number of accidents, whether swallowing a corrosive or toxic substance or an infection with one’s research material (1). A survey of 57 labs in 1915 found that 47 infections were associated with workplace practices and more than 40% of those were attributed to the practice of mouth pipetting. A longitudinal study of 921 workplace laboratory infections from 1893 and 1950 found that 17% were due to “oral aspiration through pipettes or to splashes of culture fluids into the mouth (2).”

Infection through the use of one’s oral cavity was such an occupational hazard that it warranted an article, “The Hazards of Mouth Pipetting,” from two gentleman working for the U.S. Army Biological Laboratories. In 1966 they wrote,

although the use of pipettes in the early chemistry laboratories undoubtedly led to accidental aspiration of undesirable toxic and poisonous substances, the first recorded laboratory infection due to mouth pipetting occurred in 1893 … [with] the case of a physician who accidentally sucked a culture of typhoid bacilli into his mouth …

compared with the equipment and procedures required to avoid other types of microbiological laboratory hazards, the method of avoiding pipetting hazards is so elementary, so simple, and so well-recognized that it seems redundant to mention it [emphasis added by author]. However, continued accidents and infections in laboratories illustrate, even today, that there is a lack of acceptance of the simple precautionary measured needed (2).

By the 1970s, mouth pipetting had fallen out of favor as swanky, mechanically adjustable and cheap pipettes flooded the market (3). They were not only infinitely safer but also far more accurate. Instead of drawing a semi-approximate volume of solution with the imperfect measuring device that is your mouth, standardized and calibrated pipettes were available that could zip up a solution to one’s desired volume. More precision. Better experimental results. Less contamination. More ergonomic. Fewer infections. Nowadays, mouth pipetting is explicitly banned from laboratories.

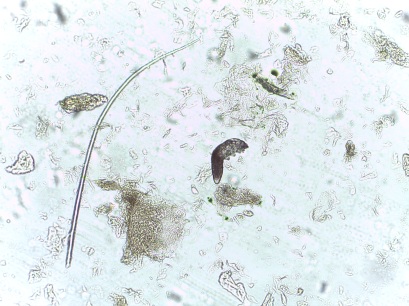

A woman mouth pipetting to select specimens of ectoparasites. Source: National Library of Medicine

And, indeed, you might think that this old school technique is thankfully old news and good for a giggle but mouth pipetting is still practiced in some countries. A study looking at the lab practices and biosafety measures of Pakistani lab technicians found that mouth pipetting was reported by 28.3% technicians (4). This paper was published just last year, in August of 2012. Another study in 2008 found that Nigerian technicians working in clinical laboratories were not only improperly vaccinated against many of the preventable diseases that they were testing for (!) as well as eating and drinking in the lab but 1 in 10 also reported mouth pipetting (5).

Lest you think this is just happening in developing countries, be rest assured that American teenagers and young adults will always find a creative way to jeopardize their health. In 1998, a 19-year-old nursing student in Pennsylvania was hospitalized for several days following infection with a unique strain of Salmonella paratyphi she was working with in a lab; the case report strongly suggests that mouth pipetting was the culprit behind this particular microbial misadventure (6).

Another article from 1995 assessing lab accidents found that 13% of laboratory-acquired infections were a result of mouth pipetting. That’s 92 accidents attributed to someone in a lab deliberately putting a pipette or capillary tube into their mouth and sucking up some solution laden with microbes (7). Clearly, we still have a way to go in dissuading people to stop using pipettes as straws.

A technician mouth pipetting environmental water samples in Malta. Image: E Mandelmann. Source: History of Medicine

Mechanical manual pipettes have been a godsend to technology and the sciences, saving researchers time and resources in measuring and transferring liquids. Pipettes now serve as an icon of the scientific pursuit of knowledge – we’re all familiar with the close up of the gloved hand and pipette tip hovering over some glowing liquid. It’s banal, efficient and ubiquitous. It’s the dogged, unsung hero of the lab but there were several decades when our method of pipetting was also a microbial misadventure in the waiting.

Resources

“There are reports of laboratory infections by means of the pipette with quite a variety of microorganisms. In the intestinal group: typhoid, Shigella, salmonella, cholera; among others, anthrax, brucella, diphtheria, hemophilus iniluenzae, leptothrix, meningococcus, Streptococcus, syphilis, tularemia; among viruses, mumps, Coxsackie virus, viral hepatitis, Venezuelan equine encephalitis, chikungunya, and scrub typhus.” Download this neat article on the history and epidemiology of lab-acquired infections here.

Want to see more pictures of mouth pipetting? Of course you do! I’ve been collecting them on the Body Horrors tumblr here, here, here, here and here. Here’s a sign. And here’s a riff on a meme.

References

1) AG Wedum. (1997) History and epidemiology of laboratory-acquired infections. J Am Bio Safety Assc. 2(1): 12-29

2) Phillips GB &Bailey SP (1966) Hazards of mouth pipetting. Am J Med Technol. 32(2): 127-9

3) JA Martin (April 13, 2001) The Art of the Pipette BiomedNet Magazine. 100

4) S Nasim et al (2012) Biosafety perspective of clinical laboratory workers: a profile of Pakistan. J Infect Dev Ctries. 6(8): 611-9

5) FO Omokhodion (1998) Health and safety in clinical laboratory practice in Ibadan, Nigeria. Afr J Med Med Sci. 27(3-4): 201-4

6)B Boyer et al (1998) The microbiology “unknown” misadventure. Am J Infect Control. 26(3):355-8

7) DL Sewel (1995) Laboratory-Associated Infections and Biosafety. Clin Micro Rev. 8(3): 389-405

HILL, N. (1999). Laboratory-acquired Infections: History, Incidence, Causes and Preventions, 4th edition. Eds. C. H. Collins and D. A. Kennedy. Butterworth Heinemann, Oxford 1999. Pp. 324. ISBN 0 7506 4023 5. Epidemiology and Infection, 123 (1), 181-181 DOI: 10.1017/S0950268899002514